The Definitive Munich Street Photography Guide (with pictures)

written by Leonardo Bertoldi

Whether you’re visiting Munich or live there, this article offers a practical way to navigate some of the city’s most photogenic neighbourhoods and spaces for street photography. Rather than a simple list of locations, it proposes a way to read the city through its architecture and public spaces, encouraging you to explore and photograph it with intention, whether using a camera or a smartphone.

Each of the five sections below can be approached as a standalone photography walk, centered around a specific theme.

1. The legacy of the Kingdom of Bavaria

1806. That is the year that Bavaria became a modern independent state. More than two centuries later, the architectural landmarks of its Kingdom are still very much present, providing a historical background to the contemporary crowds walking in the old town carrying a Louis Vuitton shopping bag.

Max-Joseph-Platz is an ideal starting point for exploring Munich through its architecture. The area offers multiple photographic opportunities thanks to the close intersection of the Residenz, the Nationaltheater, and the linear power display of Maximilianstraße, where Maximilianstil architecture frames a long perspective now occupied by luxury stores and hotels. In the late afternoon, light creates long, sharp shadows along the columns of the Nationaltheater facade, interacting naturally with the steady flow of people attending performances or passing through the square. In the evening, the Residenz Theatre becomes particularly cinematic, with its bright red neon sign and fully transparent glass front standing out against the surrounding classical architecture. Silhouettes emerging against the backlit facade can result in strong and cinematic images.

Along Maximilianstraße, beyond the presence of supercars and well-dressed shoppers, long shadows often cut across the street almost perpendicularly, reinforcing the strong sense of order and perspective that defines the space. Tram line 19 and the steady presence of cream-coloured Mercedes taxis add another layer to the scene, often helping to anchor compositions and introduce movement against the rigid architectural backdrop.

On the opposite side of the Residenz lies the Hofgarten, the former royal garden now open to the public, where long colonnades lend themselves to almost abstract compositions shaped by light and repetition. On weekends, the garden fills up with people playing bocce or lying on the grass with a book, providing a wide variety of subjects to work with for capturing interesting moments.

About a 20-minute walk from Hofgarten, Königsplatz is another square worth exploring. Defined by monumental, Greek-inspired buildings on three of its four sides, its strongest photographic opportunities come from the interaction between light and the Doric columns of both the Glyptothek facade and the Propylaea gate.

Leaving the city centre and moving west, you reach Nymphenburg, the former summer residence of the Bavarian court, now fully absorbed into the urban fabric. While construction began in the 17th century, the palace largely reflects an 18th-century layout, defined by elegant staircases and a rhythmic facade. Using the palace as a backdrop allows for strong plays of shadows and silhouettes, especially when combined with the steady flow of visitors. The residence is surrounded by a vast park which was a formal court garden and leads, after a short walk, to the Apollo Monopteros, a small classical structure that has become a well-known photographic landmark within the city.

Returning toward the city, the Maximilianeum continues this language of representation, with its neoclassical facade dominating the opposite end of Maximilianstraße. For street photography, using a longer focal length helps compress the perspective, allowing human figures to be framed against the building’s monumental symmetry and emphasizing differences in scale. During golden hour, the light becomes particularly striking, bathing the facade in warm tones that can shift toward a burnt orange appearance.

What remains of the Bavarian Kingdom today is not only a set of traditions, but an architectural legacy: a built framework that still directs movement, scale and perspective across Munich’s streets.

2. Post-war modernism and functional spaces

After World War II, Munich shifted from monumental representation to architecture driven by function and social ideals. A key turning point arrived with the 1972 Olympic Games, which pushed the city to embrace modernist ideas and large-scale projects designed with an international outlook.

Olympiapark is a strong example of late modernist architecture, defined by its translucent glass structures and flowing, high-tech lightweight forms. These surfaces interact constantly with light, creating reflections, overlaps and semi-transparencies that work particularly well with human figures passing by. The park naturally supports everyday activity, from runners and people relaxing by the Olympic Lake to the many events that take place during the summer months, offering layered scenes where architecture, park landscape and human presence intersect, resulting in naturally cinematic scenes.

This architectural language extends beyond the park itself and continues into the adjacent Olympic Village, located on the other side of the Mittlerer Ring. While it features some brutalist elements, Munich’s Olympic Village reflects a broader post-war modernist approach, combining exposed concrete with social and functional ideals that embody the late-1960s vision of an ideal future. The neighbourhood offers a wide range of striking angles, framing opportunities and smaller details, including the first-ever Olympic pictograms designed by Otl Aicher for the 1972 Games, celebrated for their colour-coded clarity and functional logic. Within the overall complex, residential buildings, university housing, shops and even a church coexist in a cohesive urban structure, reinforcing the idea of a neighbourhood designed around human scale. Everyday scenes, from students heading to the library to locals shopping or skaters passing through, provide a constant flow of photographic subjects. Focusing on the interaction between concrete surfaces, colour-coded pipes and signage, and the people moving through them can result in interesting compositions.

Heading back toward the city centre, at the southern edge of the Englischer Garten, Haus der Kunst plays a comparable role within the city, having been repurposed from its original World War II era function into a contemporary art museum. Its architecture follows a very different direction compared to the Olympic Village, yet its post-war role has similarly been functional, serving the community as a cultural institution and reflecting Munich’s forward-looking attitude. The building’s monumental scale, combining references to Greek temple architecture with the visual language of 1930s regime propaganda, creates a striking and complex backdrop for photography. In summer evenings, the Doric colonnade on the rear side of the building becomes particularly cinematic. The many exhibitions also offer a wide variety of visual backgrounds that you can explore with your camera.

Post-war architecture becomes a framework for routine, offering street photography a setting where function, light and human presence intersect.

3. Contemporary Representation

I see contemporary Munich as a rational, collected and forward-looking city that still holds tightly to its traditions. An economic powerhouse determined to position itself as international across multiple sectors. This tension is what drew me to move here, and it directly shaped what I look for in my street photography. Brands become the dominant form of representation in the contemporary timeline of urban landscape.

Iconic buildings such as BMW Welt, located in the northwest of the city, embody this balance clearly, presenting progress as inevitable while carefully integrating it with tradition through fluid forms and a crystalline glass aesthetic. The result is architecture that lends itself to near-abstract compositions, where clean surfaces are briefly interrupted by visitors moving through the space, looking at the latest BMW models.

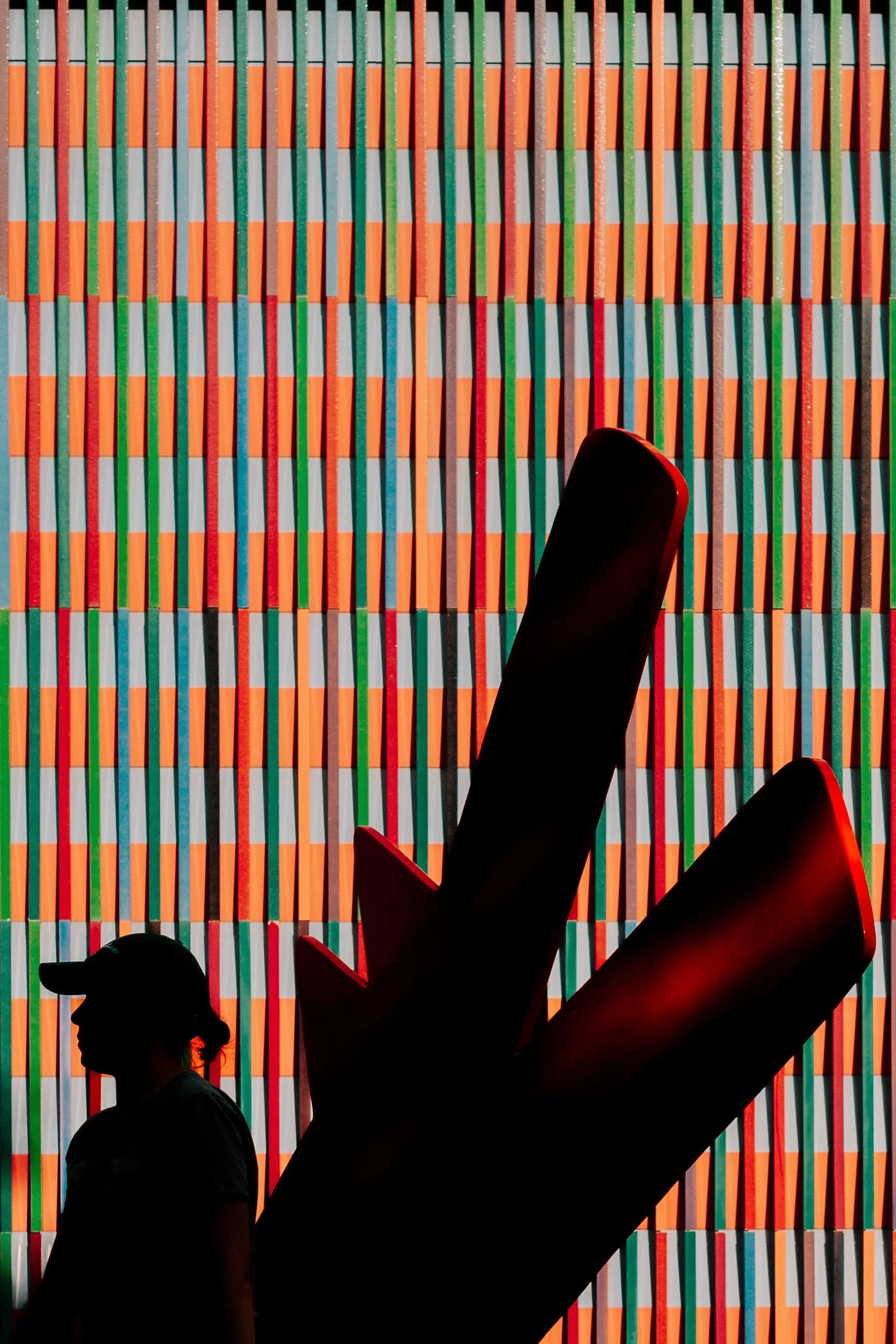

The Brandhorst Museum, located in the Museum Quarter, translates culture into a bold, colourful architectural statement, housing a contemporary art exhibition space. Its vertical ceramic tiles wrapping the four facades create a striking backdrop where silhouettes and light interact with the building’s textured surface. In warm summer evening light, the bright red Keith Haring dog sculptures work as reduced graphic elements against the museum’s saturated surfaces. The overall composition becomes flat and almost two-dimensional, functioning as a visual field briefly interrupted by passing figures, largely independent of the exhibition taking place inside.

The HVB Tower at Arabellapark represents a restrained form of contemporary corporate architecture. Its vertical mass and repetitive facade convey efficiency and control in a cold, collected manner. For street photography, the area works through differences in scale and compression, with small human figures moving in front of the monumental office blocks, where power is clearly present but never overtly staged.

Heading south into the former industrial area of the Schlachthofviertel, in the Ludwigsvorstadt–Isarvorstadt district, Volkstheater offers a quieter take on contemporary architecture, defined by clean lines and a restrained use of brick that feels deliberate. Designed as a public cultural institution, the building prioritizes accessibility, hosting theatre productions while remaining open at street level. The large central arch on the facade acts as the main visual anchor that together with the brickwork creates an industrial yet refined surface for light to interact subtly. For street photography, it offers human figures moving across a carefully composed background that feels public, functional and intentionally non-monumental. Other everyday locations like Leonrodplatz reveal the same dynamics at a more ordinary scale with routine, movement and light shaping an otherwise unremarkable urban intersection.

Contemporary architecture in Munich operates as representation first, leaving street photography to reveal what happens in between its polished surfaces.

4. Underground and waiting spaces

Contrary to the previous sections, which focus on architectural eras designed to convey a message, Munich’s U-Bahn (Underground) reveals spaces meant to be waited through rather than observed. As classic non-places, underground stations function as empty shells defined by continuous movement, identical lighting conditions and a suspension of time, largely unaffected by season or hour. Despite the uniformity, each station introduces a subtle layer of identity through patterns, colours and graphic choices, creating small variations within a rigid design template. This balance between repetition and distinction makes Munich’s underground network particularly compelling, turning each station into a contained visual system with its own photographic potential. We’ll now look at some of the most distinctive stations, focusing on design choices and how they translate into street photography.

First and foremost, Westfriedhof is the most cinematic station in Munich’s entire U-Bahn network. Its identity is defined by the large red and yellow circular ceiling lamps designed in the late 1990s by lighting designer Ingo Maurer, combined with the deep blue illumination running along the tracks on either side of the platform. This distinctive lighting setup makes the station instantly recognizable and an ideal playground for street photography, with the circular lamps acting as natural frames for passing figures. The proportions of the space naturally push compositions upward, encouraging low-angle shots to emphasize colour, scale and repetition.

Next is Marienplatz, the busiest station in the network, where U-Bahn and S-Bahn lines intersect. Here, a saturated orange dominates the space, turning the station into a graphic backdrop for the controlled stream of people moving through this non-place. The wide underground tunnels, made famous by their appearance in the Arctic Monkeys’ Four Out of Five music video, work particularly well as backdrops for dense crowds and monochromatic silhouettes. The station also features mirrors that can be used to compose shots, although their often dirty surfaces and layers of graffiti require a more creative and adaptive approach.

Georg-Brauchle-Ring moves in a very different direction. Quieter and far less crowded, the station is defined by its high ceiling, vast central chamber and extended platforms. Large, multicoloured checkered walls dominate the space, reducing waiting passengers to small, isolated figures within the monumental scale of the architecture. From a street photography perspective, the focus shifts to framing people against these coloured surfaces and exploring the contrast between human scale and the overwhelming vastness of the space.

Münchner Freiheit is another striking station design, extending both underground and at street level through its integrated tram stop. It sits on the busier and more chaotic end of the spectrum, defined by constant movement and overlapping flows of people moving between metro lines and the surface. Underground, green and blue tones dominate the space, enhanced by translucent surfaces and mirror-like ceilings that create distorted reflections. At street level, the station canopy is the main attraction, with its flowing lines shaping how people move and wait for their tram. Both layers offer strong opportunities for street photography, working through reflection, repetition and the tension between structure and crowd dynamics.

Finally, a couple of stations worth mentioning, even if they don’t reach the same level of visual impact as the ones discussed above. Isartor U-Bahn station, recently renovated, now reveals its full potential through multi-level layout and a strong yellow and green colour coding. Staircases leading to the surface create interesting shadow patterns that work well for minimal compositions. Ostbahnhof, Munich’s eastern railway station, offers a different kind of atmosphere. Its long underground corridor, lined with red tiles, interacts effectively with the staircases leading up to the platforms, creating layered scenes shaped by constant crowd movement.

Munich’s underground shows how architecture designed for transit can still shape strong photographic moments through colour and human presence.

5. Seasonal rituals

While the previous sections focused on historical eras and architectural spaces, Munich’s seasonal rituals introduce a different kind of environment: the Bavarian tradition and collective behaviour.

There is a very specific moment at the end of September when Munich shifts pace and celebrates, for nearly three weeks, a tradition that dates back to 1810: Oktoberfest. Theresienwiese, the site of the world’s largest folk festival, turns into a dense visual playground of traditional Bavarian clothing, beer rituals, fairground rides and temporary amusement structures. Photo opportunities are abundant with very different moods depending on the time of day. The most rewarding moments are late afternoon, when long golden-hour shadows cut through the crowds, and nighttime, when the artificial lights of the illuminated rides and signs take over the scene. From traditional hats and people enjoying the rides, to single subjects isolated from the crowd and colorful game stands, visual attractions are constant and layered.

Frühlingsfest which translates to “spring festival” takes place between late April and early May on the same Theresienwiese grounds. With a much more local audience, it is a scaled-down version of its autumn counterpart, celebrating the arrival of good weather with a more relaxed, family-oriented and village fair atmosphere. For street photography it still provides a rich visual mix of colour, traditional clothing, food stalls and smaller beer tents. Its reduced scale and less busy crowds make Frühlingsfest a more intimate environment to photograph, focusing more on individual subjects than dense crowds typical of Oktoberfest. A similar variety of light applies.

Lastly, Tollwood is another recurring festival in Munich taking place both during the summer in Olympiapark and in winter at Theresienwiese. Blending live performances, artisan markets, international food stands and temporary structures, it creates a constantly changing visual landscape that once again offers a wide range of photographic opportunities. Experiencing the same festival across opposite seasons highlights clear differences in light and atmosphere, with the summer edition often proving the most visually engaging due to its open setting within Olympiapark.

In these festivals, street photography shifts from observing architecture to navigating costumes and collective behavior in a highly social setting.

Taken together, these walks offer a way to read Munich through its spaces, routines and temporary transformations. From monumental architecture to underground non-places and seasonal rituals, the city reveals itself through human presence moving across these stages. Street photography becomes a practice of paying attention to how everyday life unfolds within these frameworks. In case you’d like to bring one of these pictures into your home and support me in my journey, contact me or message me on Instagram for more info.